PHOTO COURTESY OF THE LAND

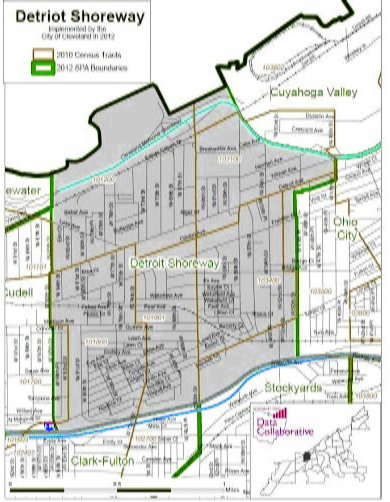

This map shows the Detroit Shoreway, a near-westside neighborhood that is just west of Ohio City, just east of Cudell, and just north of Clark-Fulton and Stockyard. Lacey Caporale, a recent PhD graduate in sociology from Case Western Reserve University, has done extensive research in the neighborhood, interviewing dozens of residents and documenting their subjective experience of gentrification. Her dissertation, “Displaced and Situated in Place: A Critical Study of Relational Space in a Gentrifying Neighborhood,” will be available to the public in May 2026.

by Lacey Caporale

(Plain Press August 2024) The Gordon Square Arts District, in the Detroit Shoreway neighborhood, is home to lively theaters, bars, and restaurants. Bright lights shine on the corner of West 65th and Detroit Avenue, as Brewnuts artisanal donuts and Superelectric Pinball Parlor invite guests to enjoy middle-class amenities.

The word “gentrification” is met with denial and skepticism by some, but one thing is for sure: Detroit Shoreway has seen an influx of middle-class residents in the last 10-15 years and the effects of the new residents, visitors, and amenities have been felt by those living in the neighborhood.

NEWS ANALYSIS

As Eli, a Black, 50-year-old resident of 10 years, told me with a chuckle, “Five or six years ago you could walk around here and you would see a few white people walking around, now you see white people walking around, jogging, walking their dogs…where are these people coming from?”

From 2015-2020, I collected ethnographic and life story interview data for my dissertation research at Case Western Reserve University. I conducted life story interviews with 33 individuals in Detroit Shoreway and had over 300 pages of single-spaced field notes. I was interested in how gentrification occurred and how residents experienced these social and economic changes. I found that the local community development organization, formally known as the Detroit Shoreway Community Development Organization (DSCDO), played a significant role in the gentrification of the neighborhood, often in partnership with the City of Cleveland.

I also found that as I moved through the neighborhood, talking with new and old residents, and residents living on the southwest side of the neighborhood, there were a variety of experiences within gentrification. Residents’ experiences of gentrification were very different based on their race, class, ethnicity, and geographic location within the neighborhood. Importantly, residents’ relation to one another shaped their experiences and understandings of gentrification in Detroit Shoreway.

As a white, middle-class graduate student, I moved easily through the gentrifying north side of the neighborhood and began interviewing many – mostly white – middle-class residents, new and old. Some of these residents outright denied gentrification or debated whether we could really consider Detroit Shoreway to be “gentrifying.” Others vehemently criticized gentrification, pointing to the physical displacement of their working-class neighbors, and limited affordable housing. In my analyses, I separated middle-class residents into two groups: liberal uplifters and social preservationists (a term coined by Sociologist Japonica Brown-Saracino).

Liberal uplifters tended to be longer-term residents, having lived in Detroit Shoreway prior to 2010. They also tended to live on the north side of the neighborhood, closest to the gentrifying area of the Gordon Square Arts District. These residents believed the social and economic changes were good for everyone, often pointing to the benefit of having less crime in recent years. Importantly, their actions in the neighborhood often encouraged gentrification. For example, many liberal uplifters engaged in self-appointed crime patrol, often working with the police to report crime ranging from prostitution to theft. Though they explained that crime was limited in recent years, they worked collectively with their neighbors to ensure that criminal activity would be responded to proactively by police.

In contrast, social preservationists were concerned that housing prices were increasing too much in Detroit Shoreway and that DSCDO wasn’t doing enough to ensure the neighborhood stayed racially, ethnically, and economically diverse. Again, perceptions of gentrification seemed to influence residents’ actions, as social preservationists worked to mitigate the negative effects of gentrification. For example, these middle-class residents personally kept their rental properties’ rents at lower costs, assisted neighbors in finding new homes when they were evicted, and worked with DSCDO to ensure new developers agreed to keep rental properties lower than market rate. Social preservationists tended to be younger than the liberal uplifters and most were new to the neighborhood, having moved to Detroit Shoreway after 2010.

All the middle-class residents were homeowners, and as a few liberal uplifters reminded me, they were not the new residents buying the expensive townhomes in Battery Park. Most held lower-ranking middle-class jobs, such as nonprofit employees, sales associates, or librarians. Middle-class residents, whether liberal uplifters or social preservationists, were in contradictory positions as they benefited from gentrification as homeowners with rising housing values but if the neighborhood gentrified too much, they could arguably be physically displaced. Either way, the middle class of Detroit Shoreway seemed to know that their voice mattered, among police and DSCDO, and they used it to encourage or mitigate gentrification. This was not lost on their working-class neighbors.

For working-class residents like Eli, “joggers,” “fancy-ass restaurants,” or “yuppies” were noticeable changes in recent years. Many of the residents in Detroit Shoreway enjoyed the new streetlights, sidewalks, and less crime. However, according to working-class residents, these changes were not made for them. Instead, working-class residents told me that these changes were only because middle-class residents were moving to the neighborhood. This research took place as gentrification was happening, therefore, I focused on indirect displacement instead of physical displacement. Working-class residents in Detroit Shoreway were able to remain physically in their homes during the data collection period, but they experienced indirect or social displacement in a number of ways.

For example, Tania, a Black, 47-year-old resident of seven years, used a Section 8 voucher to assist in paying for her apartment rent. Section 8, also known as the housing choice voucher program, is a federal program that assists low-income individuals and families, the elderly, and disabled persons in affording private-market housing. Tania told me: “They [property owners] really don’t want us over here, in here, people that have Section 8, ‘cause they think it devalues, you know, but it don’t. And it’s sad, because we should be a part of, you know, like I’m a part of this community anyway, regardless of whether I have Section 8 or not… yeah I think they’re gonna cut it. They gon’ run us right outta here.”

While Tania believed that physical displacement was imminent, she experienced indirect displacement as her concerns regarding building upkeep and a broken window were ignored by the property manager. She compared herself to her white middle-class neighbors who seemingly didn’t struggle to get what they needed in the neighborhood. Racially and economically, Tania expressed feelings of social displacement in Detroit Shoreway.

Lucy, a white, 66-year-old resident who lived near the Detroit Shoreway-Ohio City border all her life, experienced indirect displacement as well, as she watched vacant buildings fill with expensive amenities she could never afford.

Lucy explained, “[T]here’s a lot of expensive restaurants, there’s a little – there’s a hot dog spot, I don’t like hot dogs that well, then there’s Wendy’s…That’s all we have! Why couldn’t they put a McDonald’s right there? There’s a lot of things they need to change, but I’m just a peon. You know?”

I concluded that working-class residents were displaced in place, as they remained physically in their homes in Detroit Shoreway but increasingly felt that they did not belong.

The southwest side of Detroit Shoreway told a different story. While working-class residents on the southwest side were aware of the money going into other parts of the city, they did not believe they lived in Detroit Shoreway. Detroit Shoreway was one of the “nice neighborhoods,” where the councilperson lived, and safety and money were present.

The southwest side of the Detroit Shoreway neighborhood was home to more poverty and higher concentrations of Black and Latine residents. With dilapidated housing, vacant storefronts, and prostitution, it’s true that the southwest side seemed worlds away from gentrifying Detroit Shoreway. Residents could not be displaced in place because they were never in place in gentrifying Detroit Shoreway to begin with. Instead, residents said they found themselves struggling to receive basic city resources, such as streetlights and garbage cans, as well as public safety.

Some of the southwest residents believed this section of the neighborhood was purposefully contained to not interrupt the gentrification on the north side. While police seemed to swarm the southwest side, residents here told me that the police never respond to their calls. Autumn, a white 62-year-old resident of the southwest side all her life, spoke of frequent problems with prostitution and drugs on her side of the neighborhood.

Autumn explained one day she and her husband called the cops after they watched a woman, stumbling and presumably under the influence, get out of her car. “We told the cops, ‘you better check her out now before she gets back in her car and hits somebody.’ We sat here over an hour and the police never did come.”

While the north and south side of Detroit Shoreway are within the same police district, residents told me they believed police did not engage the southwest side in the same way they did the north side. Beatrix, a Black, 38-year-old resident of 21 years, told me that police, “don’t care… they beat ‘em. They take ‘em to jail for no reason. But when you call ‘em, somebody can call the police, you got a problem, they act like you getting on their nerves!” Beatrix admitted that she and her neighbors have stopped calling the police for help in addressing crime.

Southwest residents expressed feelings of neglect and simultaneous exclusion, pointing to consistent crime and a lack of public resources such as adequate garbage collection and streetlights. Travis, a white male in his twenties, even personally supplied a public garbage can on the corner of Lorain Avenue. He told me he had trouble getting DSCDO to assist in supplying one, and therefore supplied it and emptied it himself to try and curb some of the excess littering and illegal dumping. I concluded that southwest residents were situated in place, as they were left to make sense of their day-to-day lives in relation to the gentrification happening less than one mile away.

As the City of Cleveland continues to struggle to attract residents and businesses into the city, development is generally welcomed. For many, it is encouraging to see vacancies being filled with restaurants, bars, and theaters. Millions in public and private money have flooded the north side of Detroit Shoreway in the last 15 years to make the area more profitable and attract a middle-class tax base. But while working-class neighborhoods provide ample physical space (i.e., land and buildings) to purchase at low cost with high return, the well-being of many residents in these spaces is largely irrelevant, and according to the residents I interviewed, they know it. Gentrification may bring fun amenities, streetscape, and safety for some, but according to working-class residents in Detroit Shoreway, these resources are not spread evenly across the small neighborhood, let alone the City of Cleveland at large.

Editor’s Note: 1) All names in this article are pseudonyms. This article by Lacey Caporale of The Land, first appeared in the online publication The Land.:The Land is a local news startup that reports on Cleveland’s neighborhoods. Through in-depth solutions journalism, The Land hopes to foster accountability, inform the community, and inspire people to act. The Land is available online at www.thelandcle.org or via social media at: @LandofCLE (Twitter) and @TheLandofCLE (Instagram and Facebook).

Leave a reply to Michael Kilbane Cancel reply